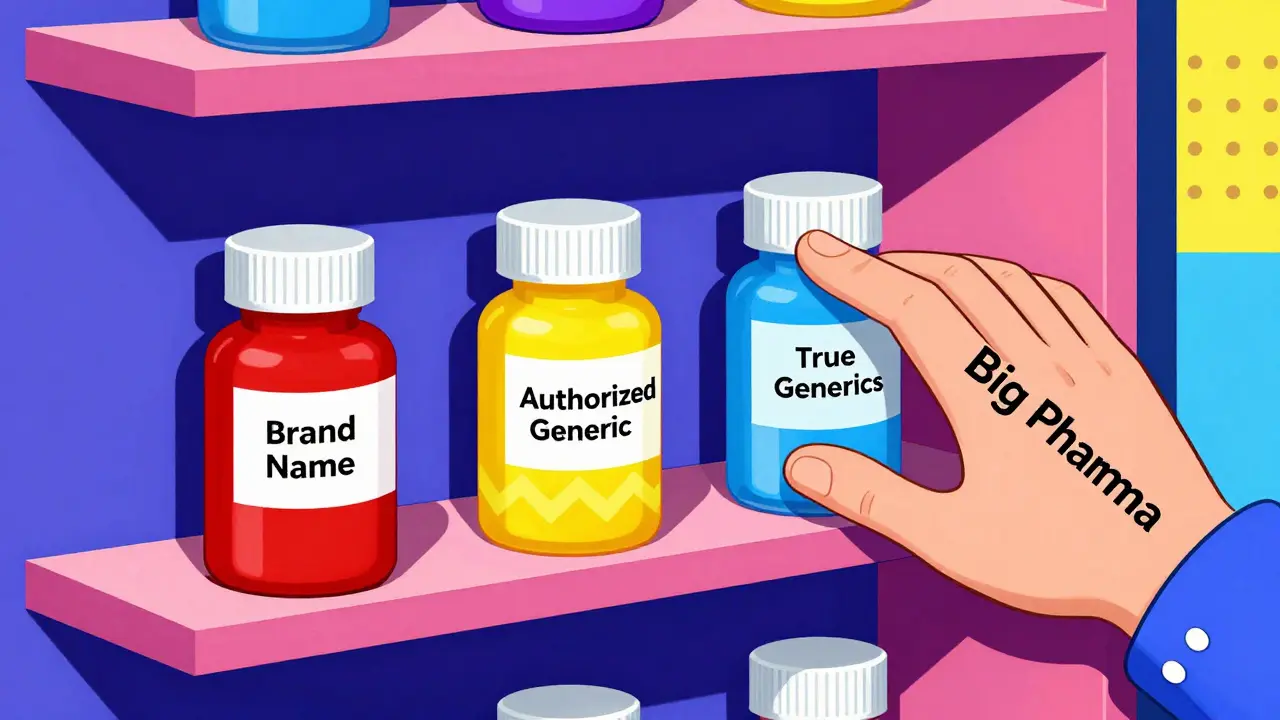

When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the promise of cheaper generic versions kicks in. Patients expect lower prices. Pharmacies expect more options. But in many cases, the first generic to hit the market doesn’t get the full benefit of its hard-won 180-day exclusivity. Why? Because the same company that made the brand-name drug launches its own version-called an authorized generic-right alongside it.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic isn’t a copycat. It’s the exact same pill, capsule, or injection as the brand-name drug, just repackaged with a generic label and sold under a different name. It’s made by the original manufacturer, or licensed to a subsidiary, and hits shelves with no new FDA review. No new clinical trials. No new data. Just a new label. This isn’t some loophole. It’s legal under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, which was meant to speed up generic access. But here’s the twist: the law gives the first generic company that challenges a patent a 180-day window to be the only generic on the market. That’s their reward for risking millions in legal fees. But if the brand company launches its own generic during that window, it shatters that exclusivity.How Authorized Generics Disrupt the Market

Think of it like this: you’re the first person to open a coffee shop in a new neighborhood. You’ve got the only location. For six months, you’re the only game in town. Then, your biggest competitor-someone who owns the original coffee brand-opens another shop right next door, selling the exact same beans, same brew, same price. Only now, they call it “Brand Coffee (Generic).” That’s what happens with authorized generics. The first generic company expected to capture 80-90% of the generic market during its exclusivity period. Instead, they often get stuck with 50% or less. The FTC found that when an authorized generic enters, the first-filer’s revenue drops by 40-52% during those 180 days. And the damage doesn’t stop there. In the next 30 months, their revenue stays 53-62% lower than it would’ve been without the authorized generic. Why? Because consumers don’t always go for the cheapest option. The authorized generic is priced lower than the brand-name drug-but higher than the true generic. So now there are three tiers: brand (highest), authorized generic (middle), and independent generic (lowest). Many patients, especially those on insurance, get the middle-tier version because it’s still covered under the brand’s formulary. The real generic? It gets buried.The Hidden Deal: Reverse Payments and Secret Agreements

Here’s where it gets darker. In many cases, the brand company doesn’t just launch an authorized generic. They pay the first generic company to delay entering the market at all. This is called a “reverse payment” settlement. Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent settlements involving first-filing generics included a promise: “We won’t launch our authorized generic if you delay your generic by three years.” These deals weren’t public. They were buried in legal documents. The total value of drugs affected? Over $23 billion. The result? Instead of generic competition starting right after patent expiry, patients waited an extra 37.9 months on average. That’s over three years of higher prices. The FTC called these arrangements “the most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior in the pharmaceutical sector.” In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that reverse payments could violate antitrust law-but it didn’t specifically ban authorized generics. So companies kept doing it, just with more careful wording.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The brand companies win. They keep market share. They keep pricing power. They turn the generic market into a controlled extension of their own brand. The first generic companies lose. They spend millions to challenge a patent, only to see their reward stolen. Teva Pharmaceutical reported a $275 million revenue shortfall in one year just from authorized generic competition on key drugs. Patients lose too. Even though authorized generics are technically cheaper than the brand, they’re not as cheap as true generics. And when the first generic can’t make money, fewer companies will risk challenging patents in the future. The Congressional Research Service found that for low-sales drugs-those making $12-27 million a year-authorized generics make generic challenges less likely. That means fewer competitors down the line. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), who negotiate drug prices for insurers, are split. About 68% say they prefer formularies that include authorized generics because they offer more pricing flexibility. But that’s because they’re playing the system, not because it’s better for patients. It’s a business decision, not a health one.Regulators Are Fighting Back

The FTC has been pushing back hard since 2011. Their reports show clear harm. They’ve opened 17 investigations since 2020 into suspicious authorized generic deals. In 2022, they made it clear: “We will challenge any arrangement that uses authorized generics to circumvent the competitive structure Congress established in Hatch-Waxman.” Congress has tried to fix this too. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act has been introduced multiple times-most recently in March 2023. It would make it illegal to agree not to launch an authorized generic in exchange for delayed generic entry. But it keeps getting stalled. Meanwhile, the industry fights back. PhRMA, the big pharma lobby, argues that authorized generics increase competition. They cite a 2024 study saying pharmacies paid 13-18% less when authorized generics were available. But that ignores the bigger picture: those savings come at the cost of crushing the only company legally allowed to be the first real competitor.

Is This Practice Declining?

Yes-but not because it’s fair. It’s declining because regulators are watching. In 2010, nearly 42% of markets with first-filer exclusivity saw an authorized generic enter. By 2022, that number dropped to 28%. A 2023 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that authorized generics were significantly less likely to launch after patent settlements. Companies are learning that the legal risk isn’t worth it anymore. Still, they haven’t stopped. Some now use third-party licensees to make the authorized generic look “independent.” Others delay launch until the last possible day of exclusivity. Some even wait until after exclusivity ends, then undercut the true generic with aggressive pricing. The Hatch-Waxman Act never imagined this. It was designed to get generics to market fast. Instead, it gave brand companies a legal tool to keep control.What’s Next?

The system is still broken. Authorized generics aren’t evil in theory. If a brand company launched a true generic at a deep discount right after patent expiry, patients would benefit. But that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is a sophisticated, legal way to maintain monopoly pricing while pretending to support competition. Until Congress closes the loophole-or the FTC successfully blocks more deals-patients will keep paying more than they should. The first generic company will keep losing. And the brand companies will keep playing the game. The real question isn’t whether authorized generics are legal. It’s whether they’re ethical. And if they’re hurting competition, why are they still allowed?Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

Yes, in terms of ingredients, dosage, and effectiveness. Authorized generics are chemically identical to the brand-name drug. The only difference is the label and who makes it. Regular generics are made by independent companies after successfully challenging the patent. Authorized generics are made by the original brand company or a company it licenses.

Why do brand companies launch authorized generics?

To protect their market share. When a generic enters, prices usually drop 80-90%. But if the brand company launches its own generic, it captures part of that market without lowering prices as much. This reduces the financial reward for the first generic company, discouraging future patent challenges and keeping overall drug prices higher.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices for consumers?

Sometimes, but not always. Authorized generics are cheaper than the brand-name version, but they’re often priced higher than true generics. This creates a middle tier that can delay the full price drop. In some cases, they help bring down prices faster. In others, they prevent true generics from gaining traction, which keeps prices higher long-term.

Is it legal for a brand company to launch an authorized generic during a generic’s exclusivity period?

Yes. The FDA and courts have consistently ruled that the Hatch-Waxman Act does not prohibit branded manufacturers from launching their own authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity period granted to the first generic filer. However, if the brand company pays the generic company to delay entry or avoid launching, that may violate antitrust laws.

What’s being done to stop anti-competitive authorized generic practices?

The FTC is actively investigating agreements that delay authorized generic entry. Congress has proposed the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban deals where a brand company agrees not to launch an authorized generic in exchange for the generic company delaying market entry. So far, these bills haven’t passed, but enforcement actions are increasing.

15 Comments

Chloe Hadland

January 22, 2026 AT 20:23i just saw my prescription price drop by 60% last month and thought wow generics are working

then i realized it was an authorized generic and my insurance still paid more than it should

Amelia Williams

January 23, 2026 AT 20:21this is such a classic corporate play

they make you think you're winning with lower prices but really they're just rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic

patients get a tiny discount while the real competition gets strangled before it even starts

venkatesh karumanchi

January 24, 2026 AT 08:37in india we dont have this problem

local generics are cheap and everywhere

no fancy authorized versions

just pure competition

why is america so good at inventing ways to make medicine expensive

Elizabeth Cannon

January 26, 2026 AT 03:38so let me get this straight... the company that spent 2 billion to make a drug gets to launch a cheaper version of it but only to screw over the actual generic company that did the hard work

and we call this capitalism

bro this is just legalized theft with a law degree

siva lingam

January 26, 2026 AT 06:59so the brand company makes a generic... wait that's not a thing

Phil Maxwell

January 27, 2026 AT 01:39i read this whole thing and just sat there thinking... wow

that's wild

but i guess i'm just glad my insulin isn't $1000 a vial anymore

Shelby Marcel

January 27, 2026 AT 10:09wait so authorized generic = same pill diff label = brand company still in control

so why do they even call it generic

its like calling a fake designer bag a "budget version"

blackbelt security

January 28, 2026 AT 23:50this is why i stopped trusting big pharma

they don't care about health

they care about spreadsheets

and patients are just line items

Patrick Gornik

January 30, 2026 AT 00:58the entire pharmaceutical industrial complex is a postmodern performance art piece where the audience pays for their own exploitation

hatch-waxman was never meant to be a market mechanism-it was a social contract

but now the brand companies have weaponized the language of competition to preserve monopoly

we are not in a free market

we are in a curated oligopoly disguised as choice

the authorized generic is the ultimate neoliberal trick: you get lower prices but you lose agency

and the worst part? you're told to be grateful

grateful for crumbs from the table they built with your tax dollars and your patents

the real crime isn't the legal loophole

it's that we've stopped being outraged

Tommy Sandri

January 31, 2026 AT 14:50the regulatory framework surrounding pharmaceuticals is inherently complex and requires careful balancing between innovation incentives and market accessibility. while the practice of authorized generics may appear anticompetitive on the surface, it is not categorically prohibited under current statutory interpretations. any legislative reform must account for the unintended consequences on investment in R&D.

Tiffany Wagner

January 31, 2026 AT 18:53i just got my meds and noticed the generic was way cheaper than last time

but now i wonder if it was really the generic or just the brand in disguise

Viola Li

February 2, 2026 AT 16:24this is why i hate america

everything is a scam

even the things that are supposed to help you

they let you think you're winning while they still win more

Dolores Rider

February 3, 2026 AT 20:07they're watching us... the pharma giants... they have cameras in the pill bottles i swear it

they know when we switch to generic and they punish us by raising prices on the authorized ones

and don't even get me started on the PBMs... they're all in cahoots... 💔

Jenna Allison

February 4, 2026 AT 21:49authorized generics are technically identical to brand drugs-same active ingredient, same bioavailability. the difference is purely in branding and who manufactures it. the real issue is market distortion: when the brand company enters as a generic, it prevents the true generic from gaining volume and negotiating power. this delays the price collapse that benefits patients long-term. the FTC data is clear-authorized generics suppress competition even if they lower prices slightly in the short term.

Vatsal Patel

February 5, 2026 AT 18:34oh so the big pharma guys are just... playing monopoly with our health

and we're surprised?

next they'll patent oxygen and sell it as 'authorized air' btw did you know your phone battery is also an authorized generic of lithium? just sayin'