When a doctor prescribes a biosimilar instead of the original biologic drug, the billing process isn’t as simple as switching one pill for another. Unlike generic drugs, which are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts, biosimilars are highly similar but not exact copies of complex biologic medicines. This difference changes everything when it comes to how providers get paid and how claims are submitted to Medicare. If you’re a clinician, pharmacist, or practice administrator, understanding how biosimilars are coded and reimbursed isn’t optional-it’s essential to avoid claim denials and lost revenue.

How Biosimilar Reimbursement Works in Medicare Part B

Medicare Part B covers drugs given in doctor’s offices and outpatient clinics, including most biosimilars. The payment system for these drugs is based on a formula: 100% of the product’s Average Selling Price (ASP) plus a 6% add-on. This formula applies to both the original biologic and its biosimilar versions. But here’s the catch: the 6% add-on isn’t based on the biosimilar’s own price. It’s calculated using the ASP of the original reference product.

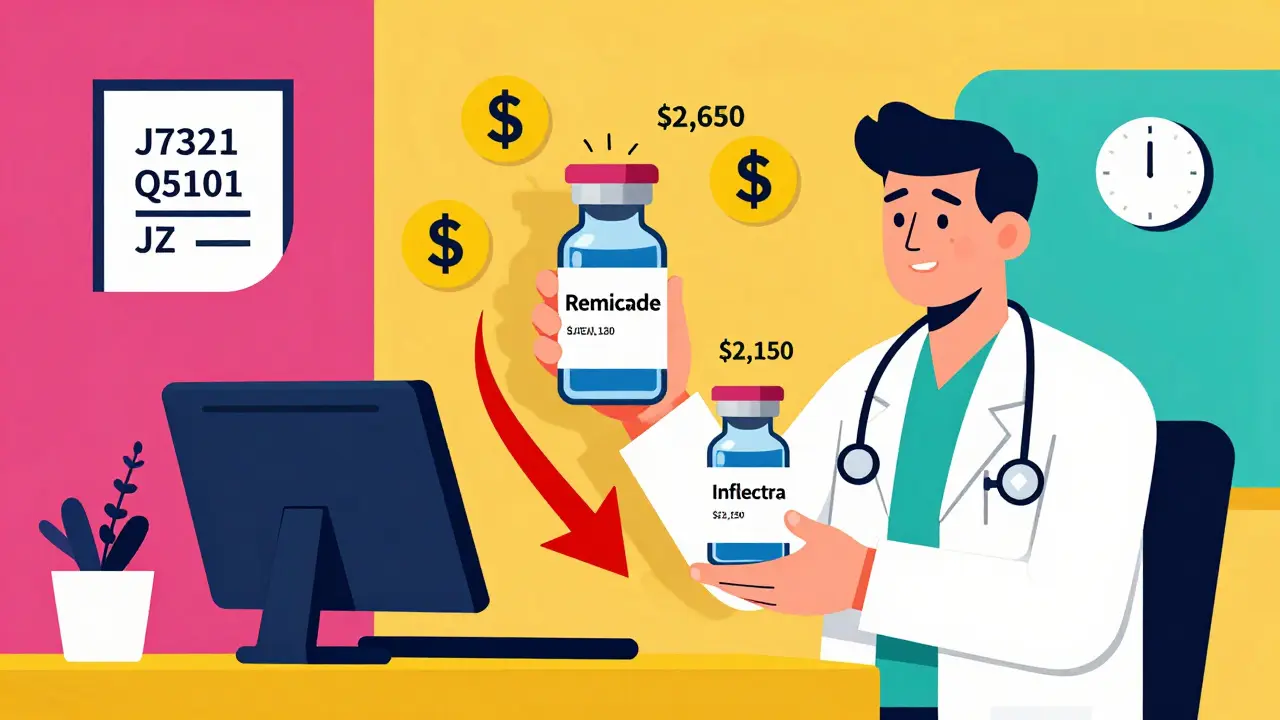

For example, if Remicade (infliximab) sells for $2,500 per dose and Inflectra (its biosimilar) sells for $2,000, Medicare pays the provider 106% of $2,500 for Remicade-that’s $2,650. For Inflectra, Medicare pays 100% of $2,000 plus 6% of $2,500-that’s $2,000 + $150 = $2,150. The provider makes $500 less on the biosimilar, even though the biosimilar costs less to buy. That $500 difference isn’t just about profit-it affects whether a clinic chooses to use the cheaper option.

This system was designed to encourage biosimilar entry into the market, but it’s created an unintended problem. Providers earn more money per dose when they use the more expensive reference product. A 2020 analysis by MIT’s Dr. Mark Trusheim found that this structure creates a financial disincentive to switch. Even when a biosimilar is 20% cheaper, the provider’s reimbursement difference is only $30 per dose. That’s not enough to overcome long-standing habits or administrative inertia.

The Shift from Blended Codes to Product-Specific Codes

Before 2018, all biosimilars for the same reference product shared one HCPCS code. For infliximab biosimilars, that was Q5101. CMS paid a blended rate based on the average price of all biosimilars on the market. That meant if Inflectra came in at $2,000 and Renflexis at $1,800, the payment was averaged out-say, $1,900. But that created a "free rider" problem. The first biosimilar to enter the market bore the cost of price competition, while later entrants rode on the lower ASP without being penalized. Manufacturers had little incentive to price aggressively.

In January 2018, CMS changed the rules. Each biosimilar now gets its own unique HCPCS code. Inflectra got J7321. Renflexis got J7322. Each is paid based on its own ASP plus 6% of the reference product’s ASP. This change gave manufacturers a stronger reason to compete on price: their reimbursement directly reflected their own market price. It also gave CMS better data to track which biosimilar was actually being used.

But this change came with a steep learning curve. A 2022 survey by the Community Oncology Alliance found that 68% of cancer clinics experienced billing confusion during the first six months after the switch. Claim denials spiked because staff were still using the old blended code. Practices that didn’t update their electronic health records or pharmacy systems saw a 12-15% error rate in billing. The fix? Dual verification: pharmacy staff confirm the drug administered, and billing staff cross-check the correct HCPCS code before submission. Clinics that did this reduced errors to under 3%.

What Codes Do You Use? J-Codes, Q-Codes, and the JZ Modifier

Every FDA-approved biosimilar gets a permanent J-code or a temporary Q-code. J-codes are for long-term use. Q-codes are temporary, used during the first few months after approval while CMS finalizes the permanent code. For example, when a new biosimilar for adalimumab hits the market, it might start with Q-code Q5103 and later switch to J-code J7620.

Since July 1, 2023, a new modifier-JZ-became mandatory for infliximab and its biosimilars. The JZ modifier means "no drug was discarded." If a provider draws up a full dose and uses every bit of it, they must add JZ to the claim. If there’s leftover drug (like from a 100mg vial used for a 50mg dose), they don’t use JZ. This was introduced to prevent overbilling for discarded amounts. But it’s added complexity. One gastroenterology practice in Ohio reported a 30% increase in billing staff time just to verify discarded amounts and update claims correctly.

Providers must check CMS’s quarterly updates. Payment rates change every three months. Outdated codes or incorrect ASP values are the #1 reason for claim denials. Fresenius Kabi, a major biosimilar manufacturer, released a 2023 coding guide that 87% of surveyed providers rated as "helpful." But only 58% of providers feel CMS’s official documentation is sufficient to handle real-world billing issues.

Why Biosimilar Adoption Is Still Slow in the U.S.

The U.S. biosimilar market reached $12.3 billion in 2022, but that’s only 18% of the total biologics market. Compare that to Europe, where biosimilars hold 75-85% market share in the same drug classes. Why the gap?

It’s not just about price. It’s about reimbursement structure. In Europe, many countries use reference pricing or tendering systems. If a biosimilar is cheaper, it gets preferred status. Providers get paid the same amount regardless of which version they use. That removes the financial incentive to stick with the expensive drug.

In the U.S., the 6% add-on tied to the reference product’s ASP creates a hidden barrier. Even when biosimilars are 28% cheaper on average, the provider’s reimbursement difference is often less than 10%. A 2023 Avalere Health analysis estimated that if the add-on were based only on the biosimilar’s ASP-not the reference product’s-utilization could jump by 15-20 percentage points.

Some experts, like Dr. G. Caleb Alexander from Johns Hopkins, argue that the current system is "necessary but flawed." The product-specific coding is good for tracking, but the payment structure doesn’t reward cost savings. MedPAC, the Medicare advisory committee, has proposed a "consolidated billing" model where all biosimilars and the reference product in a class are paid the same rate-106% of the volume-weighted average ASP. That would eliminate the incentive to use the expensive version.

What Providers Can Do to Get Paid Right

If you’re managing a clinic or pharmacy, here’s what actually works:

- Update your EHR and billing system every quarter with the latest HCPCS codes from CMS’s Physician Fee Schedule.

- Train pharmacy and billing staff to match the administered product with its exact code-no shortcuts.

- For infliximab products, always check if the JZ modifier applies. Document discarded amounts clearly.

- Use manufacturer guides (like Fresenius Kabi’s or Sandoz’s) as a reference-they’re often clearer than CMS’s official documents.

- Implement a two-person verification system: one person selects the drug, another confirms the code before billing.

Practices that followed these steps saw claim denial rates drop from 15% to under 5%. The time saved on resubmitting claims and chasing payments more than makes up for the initial training cost.

What’s Next? The Future of Biosimilar Billing

CMS is actively reviewing the 6% add-on structure. In February 2023, it issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking asking for feedback on alternatives: a fixed-dollar add-on, or removing the reference product’s ASP from the biosimilar payment entirely.

By 2025, we may see "least costly alternative" (LCA) policies for biosimilars with three or more competitors. Under LCA, Medicare would pay 106% of the lowest-priced option’s ASP, regardless of which one the provider chooses. That would be a game-changer.

Right now, biosimilar adoption in the U.S. hovers around 35% for mature products. Analysts predict it could hit 45-50% by 2027 under current rules. But if the payment structure changes, it could jump to 65-70%-closer to European levels.

The bottom line: billing for biosimilars isn’t just about paperwork. It’s about aligning financial incentives with patient care. Until providers are rewarded for choosing lower-cost options, the savings won’t fully reach patients or the system.

Are biosimilars billed the same way as generics?

No. Generics are chemically identical to brand-name drugs and use the same HCPCS code. Biosimilars are highly similar but not identical to biologics, so each one gets its own unique HCPCS code (J-code or Q-code). They’re also reimbursed differently: generics get paid at 100% of ASP with no add-on, while biosimilars get 100% of their own ASP plus 6% of the reference product’s ASP.

Why do I keep getting claim denials for biosimilars?

The most common reason is using the wrong HCPCS code. Biosimilars have unique codes that change quarterly. If you’re still using the old blended code (like Q5101 for infliximab biosimilars), claims will be denied. Also, make sure you’re using the JZ modifier for infliximab products with no discarded amounts. Always check CMS’s latest payment updates before submitting claims.

Does Medicare Advantage pay biosimilars the same as Original Medicare?

Not always. Original Medicare (Part B) pays 106% of ASP for biosimilars. Medicare Advantage plans can set their own rates, and many pay closer to 100-103% of ASP. Some plans also have prior authorization rules that delay access. Always verify payment policies with the specific plan before prescribing.

Can I get paid more by using the reference product instead of the biosimilar?

Yes, but only because of how the reimbursement formula is structured. Since the 6% add-on is based on the reference product’s ASP, providers earn more per dose when they use the more expensive biologic-even if the biosimilar is cheaper to buy. For example, if Remicade costs $2,500 and Inflectra costs $2,000, the provider gets $150 more in add-on revenue per dose from Remicade. This is a known flaw in the system, and experts are pushing for reform.

What’s the JZ modifier and why do I need it?

The JZ modifier indicates that no drug was discarded during administration. Since July 1, 2023, it’s required on all infliximab and biosimilar claims where the entire vial was used. If you open a 100mg vial for a 50mg dose and discard the rest, you don’t use JZ. If you use every bit, you do. This prevents overpayment for unused drug. Failure to use JZ correctly leads to claim denials and audits.

Next Steps for Providers

Start by auditing your last 50 biosimilar claims. Check for:

- Correct HCPCS code (not the old blended code)

- Use of JZ modifier for infliximab products

- Consistency between the drug administered and the code billed

If you find errors, schedule a staff training session using the manufacturer’s coding guides. Update your EHR templates. And don’t wait for CMS to send you an update-check their website quarterly. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s manageable if you stay ahead of the changes.

10 Comments

Ben Kono

January 11, 2026 AT 05:53So let me get this straight we get paid more to use the expensive drug even when the cheaper one works just as good? That’s not a bug that’s a feature of the system designed to keep prices high

Cassie Widders

January 12, 2026 AT 00:49Interesting read. I work in a small clinic and we’ve had a few denials since the JZ modifier started. Took us months to get it right. Now we double-check everything. Worth it.

Konika Choudhury

January 12, 2026 AT 03:16USA still stuck in the past while the rest of the world figured out how to save money on medicine. Why are we so bad at this? India got biosimilars right years ago

Darryl Perry

January 13, 2026 AT 08:55This entire reimbursement structure is a regulatory failure. The 6% add-on tied to the reference product is economically irrational and should be abolished immediately.

Windie Wilson

January 13, 2026 AT 20:20So let me get this straight - we’re incentivized to overcharge patients by using the more expensive drug because… bureaucracy? I swear if I had a dollar for every time medicine made zero sense I’d be richer than the CEOs of Big Pharma.

Daniel Pate

January 14, 2026 AT 01:41It’s fascinating how economic incentives can override clinical judgment. The system doesn’t just fail to reward cost-efficiency - it actively punishes it. This isn’t just about billing codes, it’s about whether we value patient outcomes or provider revenue. The JZ modifier is a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

Amanda Eichstaedt

January 15, 2026 AT 02:41My clinic switched to dual verification last year and our denial rate dropped from 18% to 4%. It’s annoying to train everyone but honestly? It’s worth it. I’ve seen patients cry when they find out they can afford their meds now. That’s why this stuff matters.

Jose Mecanico

January 15, 2026 AT 10:19Just wanted to say thanks for the detailed breakdown. We’ve been struggling with the Q-code to J-code transition. The Fresenius guide helped a lot. Appreciate the practical tips.

Alex Fortwengler

January 16, 2026 AT 12:46Big Pharma and CMS are in bed together. The whole biosimilar system is a scam. They want you to think it’s about savings but it’s really about keeping the gravy train rolling. The JZ modifier? A distraction. The real fix? Nationalize drug pricing. End of story.

jordan shiyangeni

January 16, 2026 AT 22:50It is both morally and fiscally indefensible that a healthcare system would structure reimbursement in such a way as to financially penalize the adoption of lower-cost, clinically equivalent therapeutics - particularly when the disparity in reimbursement is not reflective of any meaningful difference in clinical outcomes, cost of goods, or patient safety. The 6% add-on based on the reference product’s ASP is not merely an administrative quirk; it is a systemic betrayal of the Hippocratic Oath’s foundational principle of beneficence, and its persistence reveals a deeper rot within the American healthcare infrastructure - one where profit, not patient welfare, remains the ultimate arbiter of value. The fact that even a modest 20% cost reduction yields only a $30 differential per dose underscores not inefficiency, but malice disguised as policy.