When a drug hits the market, the clock starts ticking on its profitability. The primary patent-protecting the active chemical ingredient-usually lasts 20 years. But by the time the drug clears clinical trials and gets FDA approval, half that time is already gone. So how do companies keep making billions off a drug long after the original patent expires? The answer lies in secondary patents.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

Secondary patents don’t protect the drug’s core molecule. Instead, they cover things like how it’s made, how it’s taken, or even what disease it treats. Think of them as legal tweaks around the edges of the original invention. A company might patent a new pill coating that makes the drug release slowly, a specific crystal form of the molecule, or a new use for an old drug-like treating cancer instead of just nausea. These aren’t new inventions in the traditional sense. They’re often small changes, but under current patent law, they’re enough to lock out generics. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office allows them. So do most other countries-except places like India and Brazil, where laws demand real clinical improvement before granting them.How They Delay Generic Drugs

Generic drug makers can’t enter the market until every patent on the brand drug expires. That’s where the real game begins. A single drug can have over 100 secondary patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, which is the official registry of patents tied to brand-name drugs. Each one adds another legal hurdle. For example, AstraZeneca’s Nexium (esomeprazole) was a single-enantiomer version of the older drug Prilosec. The primary patent on Prilosec expired in 2001. But Nexium, patented as a new form of the same molecule, kept sales high until 2010. That’s nearly a decade of extra exclusivity-just by changing the molecular structure slightly. Another tactic? Switching the drug’s delivery method. A pill becomes a patch. A daily dose becomes a monthly injection. These aren’t always better for patients, but they’re enough to convince doctors and insurers to keep prescribing the expensive version.The Most Common Types of Secondary Patents

There are 12 recognized categories of secondary patents in pharma. The most common ones include:- Formulation patents: Protecting how the drug is packaged-tablets, capsules, extended-release, or liquid. These make up about 22% of all secondary patents.

- Polymorph patents: Covering different crystalline structures of the same molecule. GlaxoSmithKline used this to delay generics for Paxil until 2005, even after the main patent expired.

- Method-of-use patents: Claiming a new medical condition the drug can treat. Thalidomide was originally a sleep aid. Later, it got patents for leprosy and multiple myeloma. That kept it off generics for decades.

- Enantiomer patents: Isolating one mirror-image version of a molecule. The other version might be inactive or even harmful. That’s how Nexium worked.

- Combination patents: Pairing two existing drugs into one pill. This is common in HIV and hypertension treatments.

Why Companies Spend Millions on Them

It’s simple: money. A blockbuster drug like Humira, which treats autoimmune diseases, made $20 billion a year at its peak. AbbVie filed 264 secondary patents around it. The primary patent expired in 2016. But thanks to those extra patents, Humira stayed off generics until 2023. Companies invest $12-15 million per secondary patent application. They hire teams of patent lawyers and scientists to file them years in advance. Pfizer alone has over 14,000 active secondary patents. Why? Because for every billion dollars in annual sales, a company’s chance of filing a secondary patent jumps by 17%. The numbers don’t lie. Drugs earning over $1 billion a year are nearly nine times more likely to have 10+ secondary patents than drugs making under $100 million. These aren’t random filings-they’re calculated business moves.The Controversy: Innovation or Evergreening?

Critics call this practice “evergreening.” They argue most secondary patents offer little to no real benefit to patients. A 2016 Harvard study found only 12% of secondary patents led to meaningful clinical improvements. The rest? Just legal maneuvers to keep prices high. Doctors report being pressured by pharmaceutical reps to switch patients to newer versions right before generics hit. One California physician told Medscape: “It’s confusing for patients. They’re told the new version is better-but it’s just the same drug in a new pill.” Pharmacy benefit managers, like Express Scripts, say secondary patents raise their costs by 8.3% annually. That’s money taken from patient co-pays and insurance premiums. But the industry defends it. PhRMA says follow-on innovations improve safety, dosing, and access. They point to chemotherapy drugs where new formulations reduced side effects by 37%. That’s real progress. The truth? It’s both. Some secondary patents deliver real value. Others are pure profit protection.

How the System Is Changing

Pressure is building. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. The European Commission is cracking down on “patent thickets.” The WHO calls secondary patents the biggest legal barrier to affordable medicines in 68 low- and middle-income countries. Courts are also getting stricter. In 2023, a federal appeals court limited how broad antibody patents could be-a signal that vague claims won’t fly anymore. Generic manufacturers are fighting back. In 2022, they filed legal challenges against 92% of listed secondary patents. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded. That’s because the system is stacked: proving a patent is invalid is expensive, time-consuming, and uncertain.What This Means for Patients and Healthcare

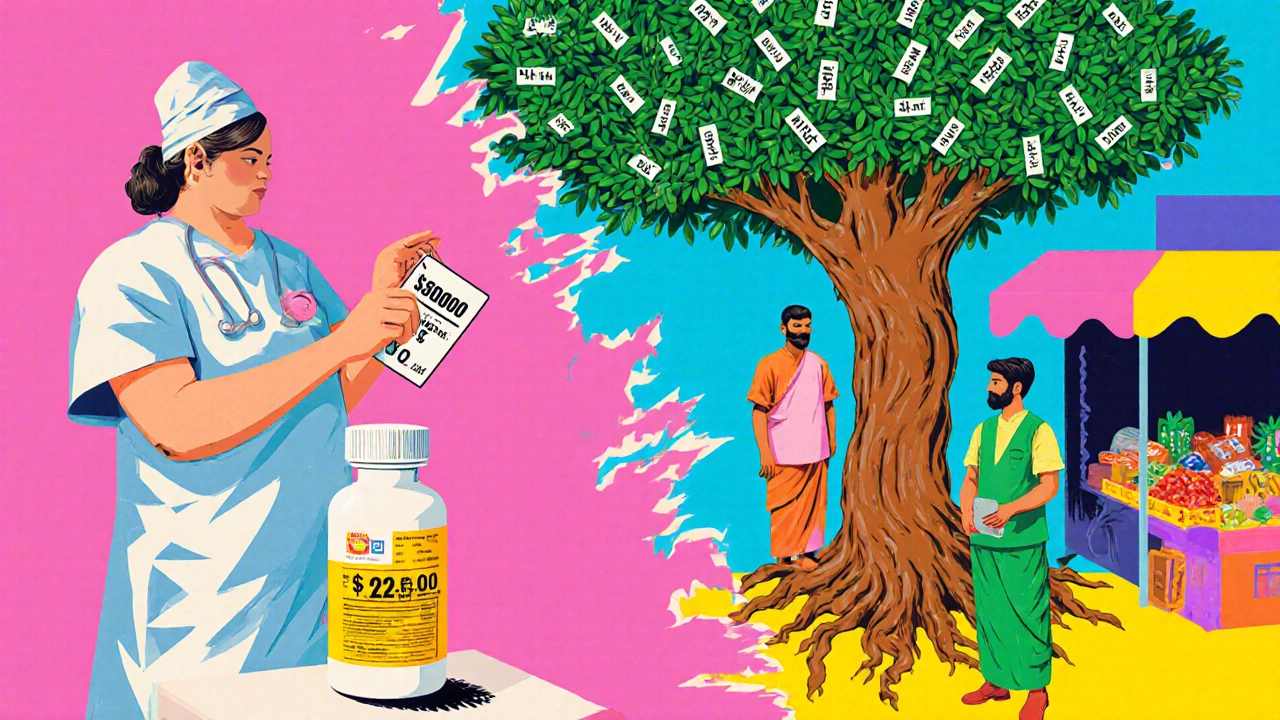

The result? Prices stay high. Patients pay more. Insurers raise premiums. Governments spend billions more on drugs that could be generic. In countries like India, where laws require proof of real improvement, generics arrived years earlier. Gleevec, a leukemia drug, cost $70,000 a year in the U.S. with secondary patents. In India, it was $2,500. The U.S. system doesn’t require proof of clinical benefit for secondary patents. That’s why so many get approved. But as public anger grows over drug prices, that may change.What’s Next?

By 2027, experts predict pharmaceutical companies will need to show real patient benefit to justify secondary patents. Otherwise, regulators and courts will start rejecting them. For now, the system still works-just not for patients. It works for shareholders. For patent lawyers. For companies that know how to play the game. The real question isn’t whether secondary patents are legal. It’s whether they’re fair.Are secondary patents the same as primary patents?

No. Primary patents protect the active chemical ingredient of a drug. Secondary patents protect modifications-like how it’s formulated, how it’s taken, or what disease it treats. Primary patents expire after 20 years. Secondary patents can extend exclusivity by many more years, even after the primary patent is gone.

Why don’t generic drug makers just copy the drug?

They can’t legally sell it until every patent on the brand drug expires. Even if the main patent is gone, secondary patents on formulation, use, or crystal structure can block them. Generic companies must either wait, pay for lengthy legal battles, or prove the patent is invalid-which is expensive and uncertain.

Do secondary patents improve patient outcomes?

Sometimes. A few secondary patents lead to real improvements-like reduced side effects, easier dosing, or new uses for old drugs. But studies show only about 12% of secondary patents offer meaningful clinical benefits. Most are designed to extend profits, not improve care.

Which countries block secondary patents?

India’s Patents Act (2005) specifically blocks patents on new forms of known drugs unless they show significantly enhanced efficacy. Brazil also requires health ministry approval before granting pharmaceutical patents. These rules helped bring down drug prices in those countries. The U.S. and EU have far more permissive rules.

How long do secondary patents delay generics?

On average, secondary patents delay generic entry by 2.3 years. For drugs with many patents-like Humira-the delay can be over 7 years. Some generics never enter the market because the legal costs are too high.

Can the government stop secondary patent abuse?

Yes, but it’s hard. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act now lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. The FDA and courts can also reject vague or obvious patents. But the system is slow, and pharmaceutical companies have deep legal resources. Real change will require stronger patent standards and more transparency.

12 Comments

Rebecca Cosenza

November 19, 2025 AT 22:57This is just corporate greed dressed up as innovation. 😒

Pawan Jamwal

November 20, 2025 AT 21:22India stopped this crap years ago. We don't let pharma companies lock down basic medicines just to make more cash. Our laws actually care about people, not profits. 🇮🇳

Cinkoon Marketing

November 21, 2025 AT 07:19So let me get this straight - a company changes the color of a pill and gets another 10 years of monopoly? That’s not innovation, that’s legal loophole bingo. I’ve seen kids in Canada ration insulin because the brand-name version costs 20x more than the generic they can’t access. This system is broken.

serge jane

November 22, 2025 AT 23:41There’s a deeper philosophical question here about ownership of knowledge. If a molecule exists in nature, even if we isolate it or tweak it slightly, who really owns it? The scientist who discovered it? The investor who funded the trial? Or the public that paid for the basic research through tax dollars? The patent system was meant to incentivize innovation, not turn medicine into a casino where the house always wins. We’ve lost sight of the original contract - innovation in exchange for temporary exclusivity, not endless legal fencing around the same damn drug.

It’s not just about cost. It’s about trust. When doctors are pressured to switch patients to a new version that’s functionally identical, and patients are told it’s ‘better’ when it’s not, the entire medical relationship gets poisoned. We’re not just paying more - we’re being lied to, systematically, by institutions we’re supposed to trust.

And yet, I still believe in science. I still believe in medicine. But I don’t believe in a system that rewards lawyers more than healers. The real breakthrough would be a patent office staffed with actual clinicians, not corporate lobbyists, who can tell the difference between a meaningful improvement and a marketing gimmick.

Maybe we need to redefine what ‘invention’ means in pharma. Is a slightly slower-release tablet an invention? Or is it just a delay tactic? If a drug treats three diseases now instead of one, is that progress - or just a clever repackaging of the same molecule? We need metrics beyond patents. We need real-world outcomes. We need transparency.

The fact that 88% of secondary patents don’t improve patient outcomes should be a red flag, not a business model. And yet here we are, spending billions to defend them. We’re not protecting innovation. We’re protecting profit. And that’s not just unethical - it’s unsustainable.

robert cardy solano

November 24, 2025 AT 21:35Humira’s 264 patents? That’s not a drug. That’s a legal fortress. I’ve seen people on it. The generic would’ve saved them thousands. But nope - lawyers made sure that didn’t happen for seven extra years. Meanwhile, people are choosing between rent and meds. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with pill bottles.

Lemmy Coco

November 26, 2025 AT 05:25so like… if a company patents a new way to make the pill dissolve… is that even a real thing? like… i feel like i’m missing something. also i think i spelled patent wrong

Nick Naylor

November 27, 2025 AT 11:49Let’s be clear: secondary patents are a necessary mechanism to incentivize incremental innovation in pharmaceuticals. Without them, R&D investment would plummet. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, under rigorous statutory guidelines, evaluates each claim for novelty, non-obviousness, and utility. The fact that some patents appear trivial to lay observers does not invalidate the legal and scientific rigor applied in their examination. Moreover, the economic reality is that 90% of drug candidates fail in clinical trials - the 10% that succeed require massive capital. Secondary patents ensure that the returns on those investments are not arbitrarily nullified by generic manufacturers who contribute nothing to the original discovery.

The notion that this is ‘evergreening’ is a populist mischaracterization. Many secondary patents enable improved bioavailability, reduced dosing frequency, or enhanced safety profiles - all of which improve adherence and outcomes. The Harvard study cited is selectively interpreted: it ignores the aggregate clinical data showing improved patient compliance and reduced hospitalizations linked to optimized formulations. To dismantle this system is to dismantle the engine of modern pharmaceutical advancement.

Brianna Groleau

November 28, 2025 AT 04:12I’m from the U.S., but I’ve lived in India and Brazil - and I’ve seen firsthand how different their systems are. In India, I met a man who was paying $30 a month for his cancer drug. Here, it would’ve been $7,000. And he wasn’t getting a worse version - it worked just as well. The difference? Their laws say: if it’s not meaningfully better, it’s not a new patent. That’s not anti-innovation - that’s anti-exploitation. We need to stop pretending that every tweak is a miracle. Sometimes, it’s just a new label on the same bottle. And we’re the ones paying for the label.

It’s not that we don’t value science. It’s that we’ve let corporations turn science into a weapon against the people it was meant to help. I’ve talked to nurses who cry because they can’t afford the drugs they’re giving. I’ve talked to parents who skip doses so their kids can eat. We can fix this. We just have to choose to.

rob lafata

November 29, 2025 AT 18:21Oh wow, so the pharma bros are just sitting in their ivory towers, filing patents like they’re collecting baseball cards? ‘Ooooh look, I made the pill blue!’ ‘Ooooh look, I changed the shape from oval to round!’ What a goddamn circus. These aren’t scientists - they’re patent sharks. They don’t cure disease, they game the system. And the FDA? They’re just the bouncers letting the rich kids into the club. This isn’t capitalism. It’s legalized theft with a white coat. And you know what? The fact that they get away with it? That’s the real disease. The system is rotting from the inside, and everyone’s too scared to say it out loud. Wake up. This isn’t medicine. It’s a Ponzi scheme with aspirin.

Matthew McCraney

November 30, 2025 AT 07:13They’re not just patenting pills - they’re patenting your health. This is all part of the Great Pharma Conspiracy. You think the FDA is independent? Think again. They’re owned by the same lobbyists who write the laws. The WHO? Infiltrated. Even the doctors you trust? Paid off with free trips to Vegas and ‘educational grants.’ They want you dependent. They want you buying the same drug for $10,000 instead of $200. And they’re using these stupid patents to keep you hooked. It’s not about science. It’s about control. They’re making you sick so they can sell you the cure - over and over again. The truth is out there. You just have to stop being brainwashed.

Bill Camp

December 1, 2025 AT 01:00Let me tell you something - America built the greatest pharmaceutical industry on Earth. We don’t need India or Brazil telling us how to do things. Our patents are the gold standard. If you want cheap drugs, go live in a country that doesn’t protect innovation. We don’t sacrifice excellence for the sake of affordability. The real villains aren’t the companies - they’re the politicians who want to destroy the system that gave us vaccines, cancer drugs, and life-saving treatments. Don’t let your anger at prices blind you to the miracle of American science.

serge jane

December 1, 2025 AT 16:37It’s funny you say that - I read your comment about the U.S. being the gold standard. But here’s the thing: if you look at the actual data, countries with stricter patent rules have faster generic access, lower drug prices, and just as many new drug approvals. The U.S. doesn’t lead in innovation - it leads in litigation. The real miracle isn’t the patents. It’s that people still believe this system works. We don’t need more patents. We need more honesty.